Basic Music Theory

Your cheat sheet for music school

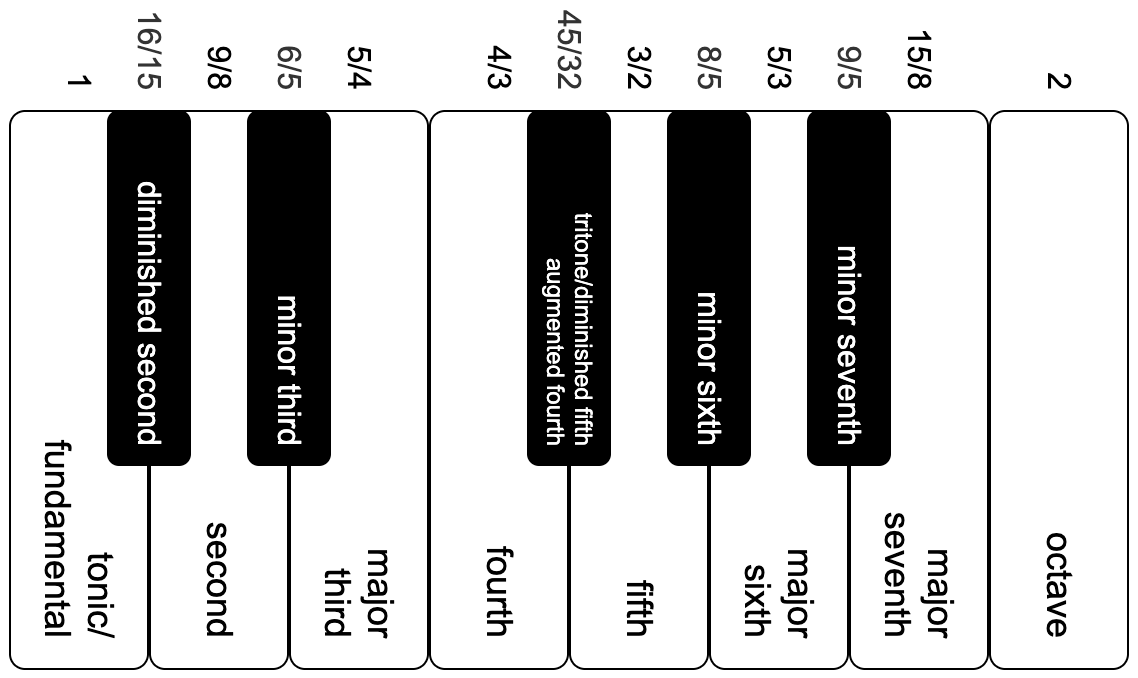

The intervals of a piano are named roughly after the distances between them. Here are the names of them relative to C (and frequency ratios explained below):

The names are all one more than the number of half-steps because they predate people believing zero was a real number and the vernacular hasn’t been updated since.

The most important interval is the octave. Two notes an octave apart are so similar that have the same name and it’s the length of the repeating pattern on the piano. The second most important interval is the fifth, composed of seven half-steps. The notes on the piano form a looping pattern of fifth intervals in this order:

G♭ D♭ A♭ E♭ B♭ F C G D A E B F♯

If the intervals were turned to perfect fifths this wouldn’t wrap around exactly right, it would be off by a very small amount called the pythagorean comma. which at is about 0.01. In standard 12 tone equal temperament that error is spread evenly across all 12 intervals and is barely audible even to very well trained human ears.

Musical compositions have what’s called a tonic, which is the note which it starts and ends on, and a scale, which is the set of notes used in the composition. The most common scales are the pentatonic, corresponding to the black notes, and the diatonic, corresponding to the white notes. Since the pentatonic can be thought of as the diatonic with two notes removed everything below will talk about the diatonic. This simplification isn’t perfectly true, but since there aren’t any strong dissonances in the pentatonic scale you can play by feel and its usage is much less theory heavy. Most wind chimes are pentatonic.

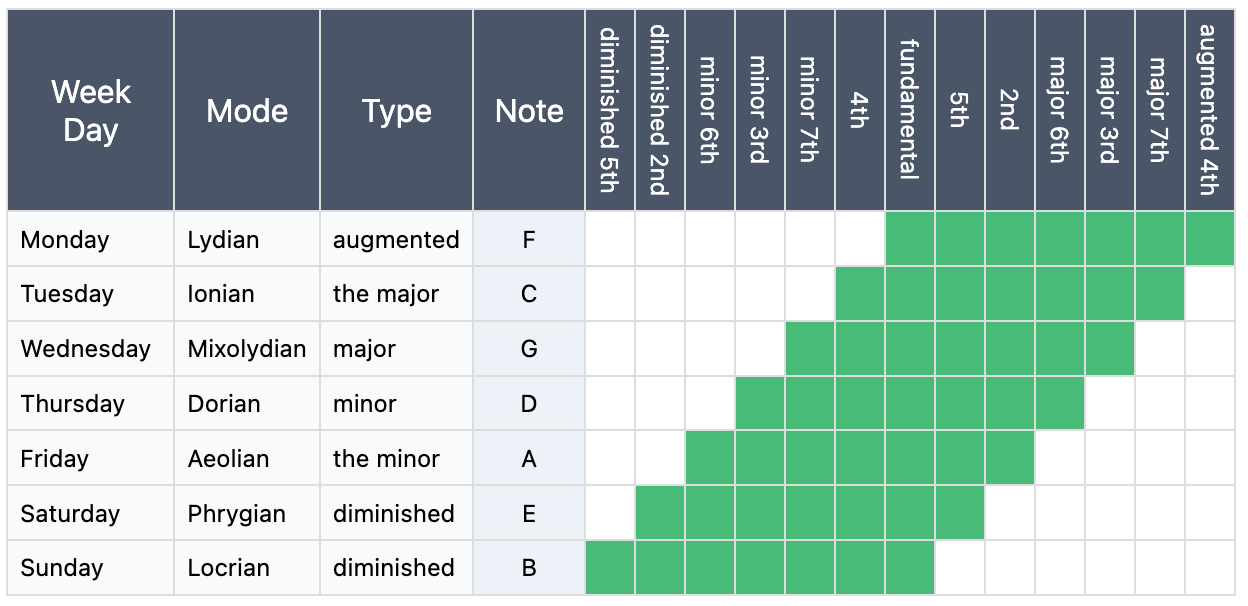

Conventionally people talk about musical compositions having a ‘key’, which is a bit of a conflation of tonic and scale. When a key isn’t followed by the term ‘major’ or ‘minor’ it usually means ‘the scale which is the white notes on the piano’. Those scales can form seven different ‘modes’ (which are scales) following this pattern:

This construction is the reason why piano notes are sorted into black and white in the way they are. It’s called the circle of the fifths.

When it goes past the end all notes except the tonic move (because that’s the reference) and it jumps to the other end.

The days of the week names aren’t common but they should be because but nobody remembers the standard names. The Tuesday mode is usually called ‘major’ and it has the feel of things moving up from the tonic. The Friday mode is usually called ‘minor’ and it has the feel of things moving down from the tonic.

The second most important interval is the third. To understand the relationships it helps to use some math. The frequency of an octave has a ratio of 2, a fifth is 3/2, a major third is 5/4 and a minor third is 6/5. When you move by an interval you multiply by it, so going up by an major third and then a minor third is 5/4 * 6/5 = 3/2 so you wind up at a fifth. Yes it’s very confusing that intervals are named after numbers which they’re only loosely related to while also talking about actual fractions. It’s even more annoying that fifths use 3 and thirds use 5. Music terminology has a lot of cruft.

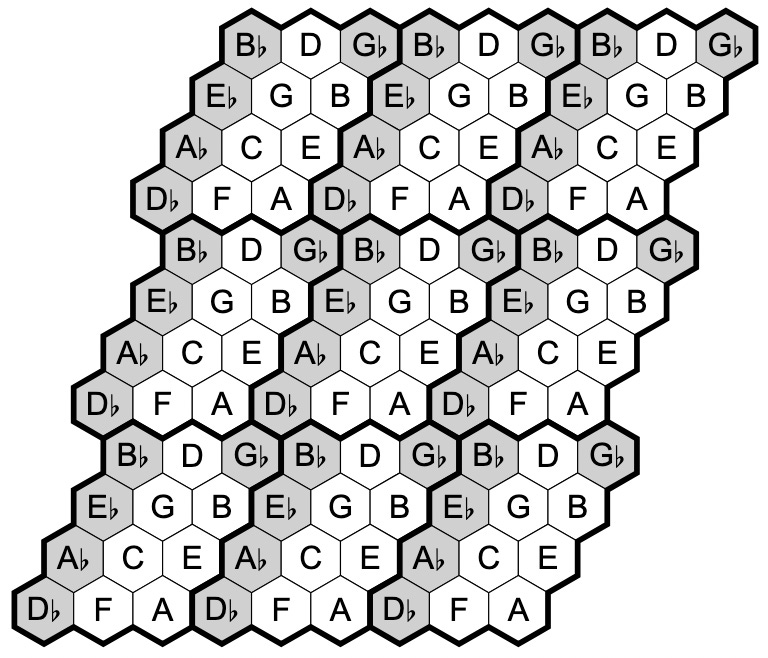

The arrangement of keys on a piano can be adjusted to follow the pattern of thirds. Sometimes electronic pianos literally use this arrangement, called the harmonic table note layout. It goes up by major thirds to the right, fifths to the upper right, and minor thirds to the upper left:

If the notes within a highlighted region are tuned perfectly it’s called just intonation (Technically any tuning which uses integer ratios is called ‘just intonation’ but this is the most canonical of them.) The pattern wraps around horizontally because of the diesis, which is the difference between 128/125 and one, or about 0.02. It wraps around vertically because of the syntonic comma, which is the difference between 81/80 and one, or about 0.01. The pythagorean comma is the difference between 3^12/2^19 and one, about 0.01. The fact of any two of those commas are small can be used to show that the other is small, so it’s only two coincidences, not three.

Jazz intervals use factors of 7. For example the blues note is either 7/5 or 10/7 depending on context. But that’s a whole other subject.

Nice post Bram.

Things nobody will tell you in music school...

Chords have these things called inversions. If you play the chord CEG, the frequency ratio of the notes is 4:5:6. But if you play the G an octave lower, you get a ratio of 3:4:5. Somebody once said that lower integer ratios are more consonant, so the second inversion of a major triad is the most consonant inversion. o_O

The minor triad has the ratio 10:12:15. Since 15 is an odd number, inverting the chord doesn't improve its consonance.

If you look at the note that ought to the be the "1" in that ratio, it's not even in the chord at all. This is the "implied fundamental". It and all of its harmonics sound good with the chord. This is why people spam the flat 6th so much in minor.

This is super helpful. I wonder if this pattern pretty much translates the same to guitar.